Dr. Emily, a young physician in a busy city hospital, passionately cared for her patients. Working in one of the busiest hospitals in the metro area, she faced a diverse patient population, each with unique needs and challenges. She noticed a recurring issue: many patients, especially the elderly and those with limited education, struggled to understand the medical pamphlets and instructions given to them. Complex medical jargon and dense text layouts often left them confused and anxious.

Studies show certain revealing facts. Adults with low literacy skills:

a) have a poorer health status;

b) their average health costs are six times higher;

c) they are less likely to comply with medication regimens; and

d) they are less likely to understand their illnesses.

These results suggest that patients are more vulnerable to grave dangers when we consider serious ailments like diabetes, heart disorder, asthma, cancer, and nerves-related sickness, etc.

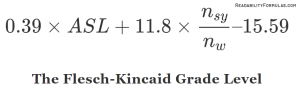

Determined to improve patient relations, Dr. Emily embarked on a mission to find a solution. Her quest led her to the field of health literacy and the use of readability formulas—tools to evaluate and improve the clarity of written text. Intrigued, Dr. Emily dedicated her evenings to studying various formulas, such as the Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level and the Simple Measure of Gobbledygook (SMOG).

Armed with this new knowledge, Dr. Emily meticulously began revising a series of patient information leaflets. She transformed complex medical terms into plain language, broke down dense paragraphs into bullet points, and used simpler sentence structures. More importantly, she ensured information was accurate and complete. The readability scores served as her guide to create materials that were more engaging and easier to understand.

According to the American Medical Association, (public) healthcare materials should be written at no higher than a 6th-grade reading level to be accessible to the general population.

The impact of these changes was immediate and profound. Patients expressed relief and gratitude, now able to comprehend instructions that once seemed like a foreign language. Mr. Jacobs, an 80-year-old with chronic heart disease, expressed his thanks to Dr. Emily. He had always struggled to follow his intricate medication regimen, but the newly revised instructions had made it clear and manageable.

Dr. Emily presented her findings at a hospital staff meeting. Her colleagues, impressed by the results, were eager to adopt these practices. The hospital administration soon integrated readability formulas into their standard protocol for creating patient materials.

A study published in the Journal of Health Communication found that improving readability of healthcare documents led to increased patient understanding by up to 30%.

Let’s explore how readability formulas have improved health literacy in the healthcare industry.

1. Hospitals in diverse locales use these tools to simplify texts, facilitating translation into various languages. In regions like Los Angeles, this practice has improved communication with non-English speaking patients.

2. With regulations like the U.S. Affordable Care Act of 2010, healthcare providers have reduced complaints and legal challenges by ensuring accessible information.

The Affordable Care Act emphasizes the importance of providing information in plain language, reflecting the legal necessity of readability in healthcare communication.

3. Readability formulas have boosted mental health treatment, as evidenced by a Chicago clinic that saw a 20% improvement in outcomes after restructuring depression therapy materials.

4. Tools like the CDC’s readability formulas have enhanced public health campaigns, such as anti-smoking initiatives, leading to increased participation.

5. Hospitals like a pediatric facility in Boston and a geriatric care center in Florida have used readability formulas to create age-appropriate materials, decreasing errors and improving patient comprehension.

A Pediatrics study highlighted that using age-appropriate materials led to an improvement in children’s understanding of their medical conditions by 50%.

6. Telemedicine platforms that use readability formulas have increased user engagement, as patients find the interfaces more navigable.

7. Community health centers, like one in New York City, have improved chronic disease management among literacy-challenged patients by applying readability formulas.

8. Using readability formulas to revise and simplify admission forms, a Texas hospital study reduced re-admission rates by 15%.

9. Institutions like a Seattle cancer center assessed and modified their written materials (like patient information sheets, consent forms, etc.) to ensure their patients could read and understand them.

As cited in the Journal of General Internal Medicine, poor readability can reduce adherence to medical instructions by 40-60%. Conversely, improved readability is associated with better patient adherence and health outcomes.

10. Organizations like the Mayo Clinic have used readability formulas to enhance patient comprehension of heart disease.

11. Bilingual health education materials in clinics such as a Miami health center catering to Cuban populations have seen increased engagement.

12. The NHS in the UK improved diabetes management by using readability guidelines, leading to 25% more patients understanding their care plans.

13. Atlanta emergency rooms used readability tools on their outpatient materials, leading to fewer callbacks.

Using Readability Tools

Health professionals can use readability tools to score the complexity of their written materials and ensure they are suitable for their audience. Here’s how to use and interpret scores:

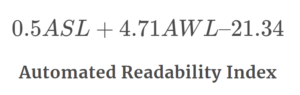

Tools: Choose a readability scoring system or readability calculator that can analyze the text. Popular formulas include the Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level, Gunning Fog Index, and SMOG Index.

Input Text: Input the health-related text into the tool. This could be patient education materials, technical manuals, consent forms, information leaflets, etc.

Assessing the Text: The tool analyzes the text for various factors, such as sentence length, word complexity, and syllable count.

Interpret the Results: Many readability tools output a grade level score, which approximates the U.S. school grade level needed to understand the text on first read. For example, a Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level of 8 means the text is suitable for an 8th-grade (around 13-14 years old) reading level.

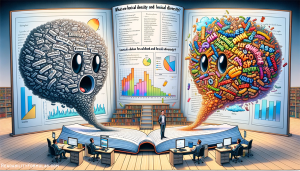

Ideal Range: Health materials should aim for a 6th to 8th-grade reading level. This level is accessible to a broad audience, including those with lower literacy skills.

High Scores: A high grade level score (e.g., 12th grade or college level) suggests the material is too complex for the general population. You might need to edit and simplify the text in plain English.

Low Scores: A low score might indicate the text is overly simplified. While simplicity is good, ensure that key information is not lost in the process.

Contextual Understanding: Readability scores are guides, not absolute measures. They do not assess the quality of the content, the appropriateness of the information, or cultural considerations.

The Art of Health Speak

Health professionals can improve health materials by writing clearly and effectively. “Clear, honest communication between patient and provider paves the way for accurate diagnoses and treatment decisions,” according to Tulane University of Public Health and Tropical Medication.

Here’s how to do it:

Tip 1

Know Your Audience: Understand the demographic, educational, and cultural background of your audience. This helps tailor the content to their needs and comprehension levels. Example: Elderly patients prefer larger fonts and simpler language. A younger demographic prefers digital formats like apps or websites.

Tip 2

Use Plain Language: Avoid medical jargon and complex terminology. Use simple, everyday language.

- Instead of “Hypertension,” use “High Blood Pressure.”

- Instead of “Administer orally,” use “Take by mouth.”

- Instead of “Adverse reactions,” use “Side effects.”

- Instead of “Tachycardia,” use “Fast heartbeat.”

- Instead of “Hemorrhage,” use “Severe bleeding.”

- Instead of “Myocardial Infarction,” use “Heart attack.”

- Instead of “Cerebrovascular Accident,” use “Stroke.”

Tip 3:

Be Concise/Specific: Be concise and precise without overwhelming readers with information. Avoid unnecessary or excessive details.

Medication Instructions

- Complex: “This medication, which is an antibiotic, should be taken four times a day, preferably after meals and not on an empty stomach, to avoid potential gastrointestinal discomfort which might include nausea or diarrhea. It’s important to complete the entire course even if you start feeling better to prevent the development of antibiotic resistance.” Readability Score: 16 [ = grade level ] | Reading Difficulty: Extremely Difficult | Grade Level: College Graduate | Age Range: 23+ year olds

- Concise/Specific: “Take this antibiotic four times daily after meals. Complete the full course, even if you feel better.” Score: 7 [ = grade level ] | Reading Difficulty: Average | Grade Level: Seventh Grade | Age Range: 12-13 year olds

Post-Surgery Care

- Complex: “After your surgery, it’s essential to monitor the incision site for any signs of infection, which might include redness, swelling, or discharge, and it’s also important to keep the area clean and dry to prevent infection. Additionally, avoid lifting heavy objects or engaging in strenuous activities.” Score: 16 [ = grade level ] | Reading Difficulty: Extremely Difficult | Grade Level: College Graduate | Age Range: 23+ year olds

- Concise/Specific: “After surgery, check your incision for redness, swelling, or discharge. Keep it clean and dry. Avoid heavy lifting and intense activities.” Score: 8 [ = grade level ] | Reading Difficulty: Average – Slightly Difficult | Grade Level: Eighth Grade | Age Range: 13-14 year olds

Dietary Advice for Diabetics

- Complex: “As a diabetic, you should consider eating a balanced diet that includes a variety of nutrients, such as carbohydrates, proteins, and fats, while being mindful of your blood sugar levels and avoiding foods that can cause spikes in your blood sugar levels, like sugary snacks and beverages.” Score: 20 [ = grade level ] | Reading Difficulty: Extremely Difficult | Grade Level: College Graduate | Age Range: 23+ year olds

- Concise/Specific: “Eat a balanced diet with controlled carbs. Avoid sugary foods to manage blood sugar levels.” Score: 7 [ = grade level ] | Reading Difficulty: Average | Grade Level: Seventh Grade | Age Range: 12-13 year olds

Exercise Recommendations

- Complex: “For optimal health benefits, it is recommended to engage in moderate-intensity aerobic activities, such as brisk walking, swimming, or cycling, for at least 150 minutes per week, spread across several days of the week, while also incorporating muscle-strengthening activities on two or more days per week.” Score: 21 [ = grade level ] | Reading Difficulty: Extremely Difficult | Grade Level: College Graduate | Age Range: 23+ year olds

- Concise/Specific: “Aim for 150 minutes of modest exercise like walking or swimming weekly. Include activities that build muscles twice weekly.” Score: 8 [ = grade level ] | Reading Difficulty: Average – Slightly Difficult | Grade Level: Eighth Grade | Age Range: 13-14 year olds

Instructions for Using an Inhaler

- Complex: “To use the inhaler, you must first remove the cap and shake the inhaler well, then breathe out fully to empty your lungs, place the mouthpiece in your mouth and close your lips around it, press down on the inhaler to release the medicine as you start to breathe in slowly and deeply, hold your breath for about 10 seconds to allow the medicine to reach deep into your lungs, and then exhale slowly.” Score: 24 [ = grade level ] | Reading Difficulty: Extremely Difficult | Grade Level: College Graduate | Age Range: 23+ year olds

- Concise/Specific: “Shake the inhaler, exhale, then breathe in slowly while pressing it. Hold your breath for 10 seconds, then exhale.” Score: 6 [ = grade level ] | Reading Difficulty: Fairly Easy | Grade Level: Sixth Grade | Age Range: 11-12 year olds

These examples show how to distill complex medical advice into clear, actionable instructions that patients can follow and understand.

Tip 4:

Organize Logically: Present information logically. Start with the most important information and follow with details. Example: A brochure about diabetes management should start with what diabetes is, followed by symptoms, and then treatment options.

Tip 5:

Use Active Voice: Write in an active voice to make the text more engaging and easier to understand.

Passive: This medication should be taken daily.

Active: Take this medication daily.

Passive: The prescription can be picked up by you at the pharmacy.

Active: You can get your prescription at the pharmacy.

Passive: Vaccinations are recommended to be received by children and adults.

Active: We recommend that children and adults receive vaccinations.

Passive: A healthy diet should be maintained by patients with diabetes.

Active: Patients with diabetes should maintain a healthy diet.

Passive: Blood pressure must be monitored regularly by patients with hypertension.

Active: Patients with hypertension must routinely monitor their blood pressure.

Tip 6:

Include Visual Aids: Use charts, illustrations, and other visual aids to supplement the text and aid comprehension.

Tip 7:

Focus on Key Messages: Highlight the main points or actions you want the reader to take away. Repeat these messages for emphasis. Example: A pamphlet about preventing infections can highlight the importance of handwashing: “Remember: Wash your hands frequently to prevent infections.”

Tip 8:

Test Your Material: Give your draft to a small group from the intended audience and ask for their feedback on its clarity and usefulness.

Tip 9:

Cultural Sensitivity: Be aware of cultural nuances and differences in health beliefs and practices. Tailor your material to be culturally appropriate. Example: In dietary advice for diabetic patients, include examples from various cuisines that cater to different cultural backgrounds.

According to CDC.gov, “Avoid dehumanizing language. Use person-first language instead. Describe people as having a condition or circumstance, not being a condition.”

Tip 10:

Feedback/Revision: Revise the materials based on feedback. Example: After distributing a new patient guide, collect feedback through surveys or focus groups and use the insights to improve the guide.

Tip 11:

Accessible Formats: Offer materials in various formats (like large print, audio, or Braille) to accommodate different needs. Example: a guide on managing asthma in formats like printed leaflets, online PDFs, and audio recordings.

During July–December 2022, 58.5% of adults used the Internet to look for health or medical information, with a higher prevalence observed among women compared with men. (source: CDC.gov)

Tip 12:

Use of Technology: Consider digital literacy and use technology (websites, apps) to disseminate information, ensuring it’s user-friendly. Example: Create a user-friendly app that helps patients track their medication schedule and offers reminders for taking pills.

—END—